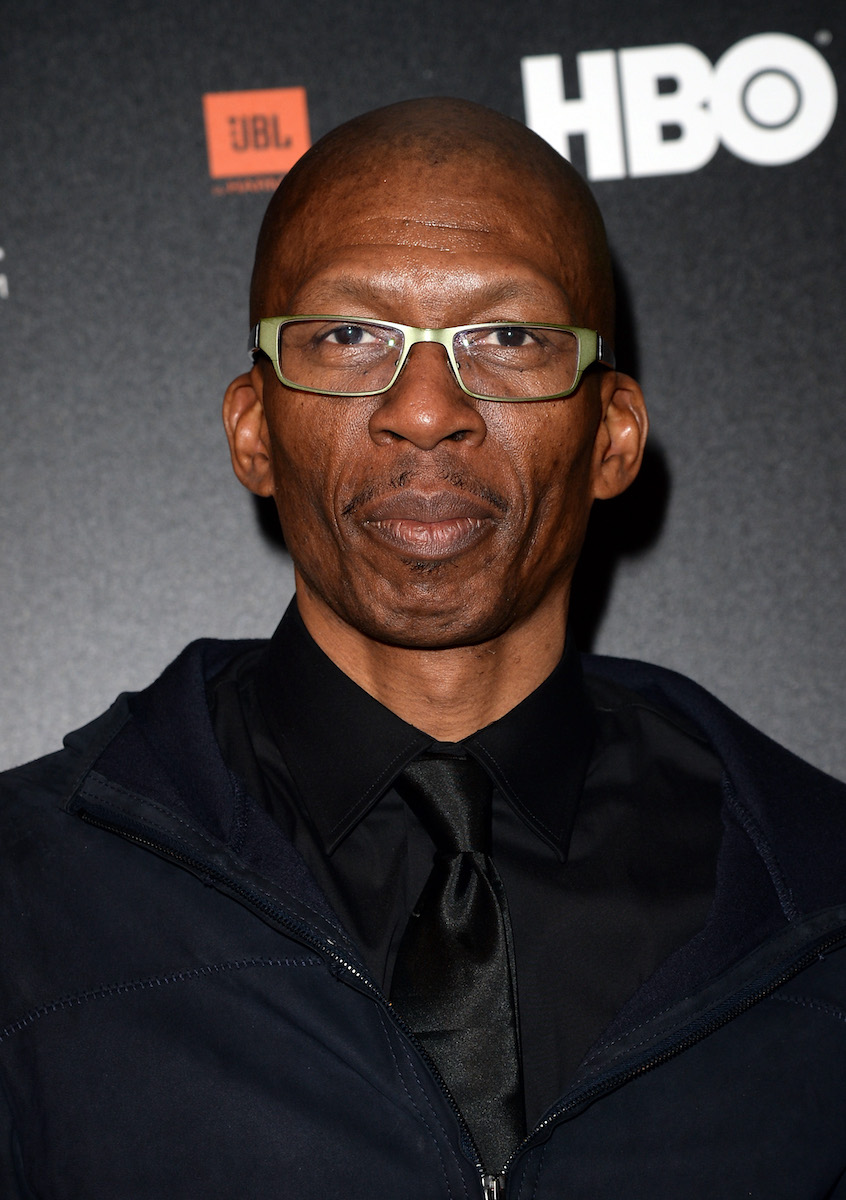

As a member of The Bomb Squad—the production crew behind Public Enemy’s genre-defining run of classic albums—it’d be an understatement to say that Hank Shocklee has had a hand in predicting and shaping the sound of the future. When Public Enemy debuted in 1987 with Yo! Bumrush The Show, they took their first step toward changing the political and sonic makeup of rap music.

On landmark albums like It Takes A Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, Fear of a Black Planet and Apocalypse 91… The Enemy Strikes Black, The Bomb Squad's beats utilized dissonance, vocal clips, and layered, chopped up-samples to create a funky and immersive tapestry of sound that has since influenced hip-hop, rock, and electronic music. With the Bomb Squad’s dense productions backing Chuck D and Flavor Flav’s polemics, Public Enemy were key in ushering in the wave of radical Black political consciousness that swept hip hop in the late 80s and early 90s.

Today, Shocklee continues the work of pushing sound forward. His latest project is the textured, evocative score that he composed for John Oluwole Adekoje’s film YE!: A Jagun Story, a pan-diasporic tale of family, war, trauma and healing. We spoke with Shocklee about everything from the Public Enemy crew’s early days as a mobile soundsystem, the production process behind crafting classic albums and film scores, and how his unique philosophy on technology and sound helps keep the spirit of adventure and experimentation in his music alive.

Before Public Enemy became Public Enemy, you were involved with the Spectrum City soundsystem. Could you tell me a little bit about Spectrum City's origins and what inspired y'all to put together a soundsystem and have a DJ crew?

Spectrum City was, and still is, a love of mine. I started out with soundsystem culture, you know? Ever since back in the days, a friend of mine back in the early 60s took a record on a turntable and played it through his brother's PA system. Now, keep in mind, my father was a jazz buff and collected all kinds of jazz records. We had high-fi precision sound system that nobody could touch.

An "in-the-house" kind of thing?

Exactly. You couldn't touch it, and he played nothing but jazz. But when my friend took a funk record, a regular R&B record and he played it on something big, it blew my mind. All of a sudden the sound is blown up and the performance comes to life. The first thing that I wanted to do was build my own soundsystem, and what does that mean?

I created my own speaker systems and I built my own speakers. I didn't build the box but I built all the components inside it and boofed 'em up. So, I would get boxes cheap and then put my own components in. I learned crossover systems, I learned amplifiers and their differences. I learned how to daisy chain them in systems. My system was a tri-amp system, which means that I had three different amps and my speaker system was in stereo. That's another thing: if you go back and listen to Pete DJ Jones, Ron Plummer, Ras Maboya—their systems was mono. Mine was in stereo, and it was huge.

You see the Jamaican soundsystems and you always see those big horns, right? I found those to be harsh, so I used all cones. But the difference is I covered the entire frequency spectrum. For example, I had eighteens on the bottom, fifteens for my mids, tens for my upper mids and five and half-inch cones with the piezo tweeters. Now, why did I go through all of that? It's because now I can replicate every frequency zone to a T. One of the problems with when you talking about speakers is that people are trying to get too much out of one particular speaker set. There's only so much you can get out of an eight-inch woofer.

Did y’all have the (Maestro) Echoplex for the voice?

We had the Roland RE-501 Chorus Echo, because everybody had the Roland RE-201 Space Echo. I wanted the 501 because it had the chorus effect on top of it. Then I saw Grandmaster Flash: he had his beatbox—the Vox V829 Percussion King—so I went and got the Roland CR-8000 and the Roland TB-303 so I could rock the bassline with the beats. At the time, Keith was DJing and we would go back and forth between each other rocking the crowd.

Y'all were doing the sound system thing as Spectrum City, but you also went in the studio and made a record called “Lies.” Could you tell me a little bit about that? And also, is the drum machine on that song an Oberheim DMX?

I believe that was the Roland TR-808. “Lies” was produced by Ray “Pinky” Velasquez. He was a dance music producer. He produced the group Twilight 22. He's the one first one that signed us and he gave us this kind of electro beat. We only had like 10 hours in the studio, so he spent 8 hours of the 10 on his electro record. I was like, "All right," but I wasn't really feeling it like that. So, I took my friend Tim Mateo in the studio with me and in two hours, we did the B-side, “Check Out the Radio”.

The Bombsquad developed its own unique approach to sampling while making the early Public Enemy albums. Can you explain a bit about how y’all worked with samples?

When I heard a lot of the older Grandmaster Flash and Treacherous Three and all those records, most of those records were done with bands. If you looked at the R&B in those days, it was all band members and maybe a drum machine. I was working with Eric Sadler in the studio and we couldn't get the programming of Clive Stubblefield down. Back then, the drum machines sounded pretty primitive—there wasn't no MIDI, there wasn't any fixing up of the timings, the swing and that sort of thing. So I said, “Look, let's just use the record."

We're gonna use parts of it, not just loop a certain portion of it. Let's use parts of it. And then from that technique, we started getting smaller and smaller chunks. It was sacrilegious to take two bars and loop it. Everything that we wanted to do had to be made from records. So, that taught us a certain understanding of textures. We never looked at records as something to jack. We looked at it for what kind of a texture that we can extract from it.

So it wasn't so much, “Oh, this has a nice bassline that I like, this has a nice drumbeat," it was more so about that textural quality that you were looking for in a sample.

Exactly. This way we can control how we want this thing to play. In other words, it's creating our own instrument out of the sound, as opposed to having the sound become the instrument. It was nothing as simple as just triggering something—it rocks for a bar or two, and then you release and you do it again—that to me was a simplistic approach to that because I wanted to get more granular. How do we get in? I want the stuff that even happens between the kick and the snare, because that gives you character as well. Sampling from the records was never about getting a clean kick or a clean snare.

A lot of people would do that, and that was their sonic signature—I understood that, I had nothing against that—but for us, I don't want something that's correct. I wanna hear a little bit before the sample, before the kick comes in. So you have to play it a different way. This is how you get flavor! (laughs). If everything is tight, then that means everything's precise.

It's uniform. There’s no tension.

Right—and if it's all precision, you don't want that. That's not what the funk is. Funk is what's off, not always what's on. The way I look at it, we're painting with sound. That's what I was looking for going into this project. PE is basically a soundtrack.

I interviewed Scott Harding a while ago and he said that when y'all were making those Public Enemy records at Greene Street, you were editing the arrangements to tape. If you wanted a horn part to drop out at a certain point, instead of doing a mute on the console, y'all would just erase that part of the tape.

You're opening up wormholes, man. (laughs). Think of it like the computer. You're doing the same thing: when you want a drop somewhere, you don't record the mute. You just go and drop it out. That's the same way we was thinking about it. I don't want the engineer to have to remember where that drop was, and I don't want him to to flub that up, because that drop has to be perfect, and it has to be perfect every time, so you cut it off. Yeah, you gotta spend time to get it right. But then once you get it right, press the boom, get rid of it. You don't even want that little bit of wind down. I don't care how small it is, it takes away the funk.

Around the time that y’all were making It Takes a Nation of Millions… and Fear of a Black Planet, I know y'all had you had your own stable of artists that y'all were working with, groups like Sons Of Bazerk and Young Black Teenagers. Did you have a lot of outside people reaching out to y'all? Like, “Yo, we gotta get The Bomb Squad for something”. I’m not necessarily talking about Ice Cube, but did y’all get other folks in the industry trying to get that PE sound?

All day. Everybody from Heavy D, you name it. Keep in mind that I'm doing PE stuff while I'm doing R&B remixes at the same time. So, I'm doing Janet, Paula Abdul, Madonna, all kinds of artists. I think that we revolutionized the remix business. Back then, it was about taking a record and basically extending it and making it longer so it could be played in clubs, and I was like, "No, no, no, no." I wiped off the original tracks and put a new track underneath, put the vocals on top of it and made it work. That right there was something that wasn't done in the R&B world.

We basically made a Bomb Squad version of remixes that had the vocals of them on it, just like you're doing today. You're taking the vocal and you just say, "Get rid of that beat. Put a new beat underneath it." The other thing that we was doing with the R&B records was putting rap in the middle of it. Rap and R&B were two different universes at that moment, so the idea was to bring those two universes together. We did the Rakim and Jody Watley remix (“Friends”), for example: when you hear and when you see it in from that perspective, now you start to understand that R&B and rap can go together.

That's what led the revolution that you hear today. The whole Bad Boy Records catalog was based off of that principle: "We gonna have the singer singing and then have the rapper come on." For a long time that was a no-no.

Oh, yeah. I remember R&B stations that wouldn't play rap. They hung their hat on that and would advertise, you know, “no rap workdays” or whatever. I don't think young people today understand how far apart hip-hop and R&B really were back then.

That's right. Doing those records got me to work with Bell Biv Devoe. Hiram Hicks was managing Michael Bivins, Ricky Bell, and Ronnie DeVoe. He brought them and said, “Hank, I got my boys here. I want y'all to produce 'em.” He heard what we was doing with remixes and got us to work with BBD and actually craft it where it was, where you couldn't tell the difference between whether they were singing or rapping. Now that formula is used widely today—what is Drake? Is Drake an R&B singer, or is he a rapper? I don't know. But it's hot! (laughs)

You’re known by so many of us as a producer with The Bomb Squad and for working on all those Public Enemy records, how did you first become interested in film scoring? What drew you to the idea of writing music for films?

I've always been a big fan of film. I came up in the early days of television and when I was six years old, I couldn't wait to run home and watch Batman And the Green Hornet. I was always intrigued with film, that was the natural progression. If you go back and listen to a lot of the PE records, they're all based off of films.

How so?

I never went into a studio and looked at it from a beat perspective. All the PE records were soundtracks. I wanted a soundtrack for cats like yourself. When you're walking down the street, you don't necessarily want to hear a song. You don't necessarily just wanna hear a beat, but you want to hear a soundtrack, your theme music for how you feel today. That's what we was going for. The transition between that and film is natural because now we have an image to work with.

How did you and John Oluwole Adekoje meet and start working together on this film?

I met John at Boston's Arts Academy—he's a professor there teaching film—and I came in as a guest speaker for the class, and we hit it off. We kind of lost touch for a minute, but when he had a film that he cut, he called me up and said, “Yo, man, I got this piece. I want you to check out and see if you dig it.” There was no sound design in it, but the picture was right on. He did it in 4K, so it's beautifully shot. My first inclination was okay, so where do you start?

What were some of the main tools you used to work on the score for YE! A Jagun Story?

I started out in Logic—it's beautiful in terms of how it handles the arrangement window. The arrangement window is like the key to Logic: it's like the best arrangement window on the planet. I used a combination of audio, synths and sound design. I've probably used mostly every technique I know in the book to make it. The film had a natural ambience because the audio recording process was not as clean as it could have been. What I did was I suppressed most of the noise that's there, then I used that noise as a guide for how I'm gonna paint the sound in it.

I also used Spectrasonics Omnisphere—the one thing that Omnisphere offered me was the ability to change its master tuning. It has massive amounts of layers that I can put together and create new kinds of textures that haven’t been done before. I've put things onto tape, run the tape backwards, then re-recorded that back in, things of that nature. I use the Earthworks microphones, their range goes from 7 Hz to 50K. That way you get, you get all the low rumble stuff, and you also get the stuff that you don't even really hear, but you perceive in the mix.

I have my trusty AKAI MPC 2500 that I love to use on everything. I also use my EMU SP-1200, which I don't use for beats as much, but for sounds, cause I like the bit rate on it. There's a totally different thing when you have an instrument that does a certain sampling bit rate, as opposed to you putting something inside the computer and then putting a bit crusher on it. Those are two different sounds. I'm not gonna sit and say which one is better or worse, but it's just a different sound. And if you want that real dusty sound, then you gotta go to that.

Yeah, the artifacts that it adds to the sound. It’s almost physical.

Exactly, you can almost hear the bits being pulled apart. The other thing I used was my AKAI S3000, which does something that no sampler does: It seamlessly samples. When you take the beginning of one sample and the ending of another, you can put that ending so close together that when it loops it, it's an infinite loop. When you take a small sound and loop it, it goes on indefinitely and it feels like it's lifting off as opposed to staying in a straight line. It's not so much of the equipment you use, it’s how you use them and what's the purpose that you're using them for.

How did you start? And could you talk about the nuts and bolts stuff like some instruments and techniques that you employed to execute this score?

When I look at a film, the first thing I wanna do is say, “Okay, where's the heartbeat of this film?” And that's when we realized that Fela Kuti’s “Trouble Sleep Yanga Wake AM” was the heartbeat. Then all I needed to do is just add the rest of the body—the lungs and everything else. I used that as the motif for the whole film. Now, when you see it or listen to it, you're not gonna really notice that it came from there. So, it was taking the vibrations of the African experiences but making it from a Nigerian-American perspective, kind of looking back at home. Now that experience is mixed in with hip hop, a little bit of funk, a little bit of R&B.

I want the transitions to be seamless, just like a mix, right? Just like you mixing two records together. You wanna make sure that the transition between scenes and emotions is so smooth and seamless, that the viewer don't even recognize these things that's happening. All of a sudden, the mood is changing and you're feeling a certain way. Sometimes you wanna feel a little sarcastic. Sometimes you wanna feel a little happy, a little surprised. But then sometimes you wanna feel a little unsure. Those are emotions that you have to hit while you're going through this journey.