In 1981 the look and sound of pop, rock, and R&B were forever altered by the arrival of a radical new step in musical tech: the Simmons electronic drum kit.

With the Simmons SDSV, co-creators Dave Simmons and Richard James Burgess found a way to combine the limitless tonal possibilities of electronic drums with the visceral feel and look of a real drum kit. Slim hexagonal pads triggering electronic sounds replaced the traditional drum kit, creating an iconic, futuristic image and an ultra-modern sound that dominated MTV and radio throughout the '80s.

The roll call of the '80s Simmons acolytes is endless. Pop sensations like Spandau Ballet, Duran Duran, Culture Club, and INXS; rock 'n' roll dragon-slayers Van Halen, Def Leppard, and Rush; R&B stars like Cameo and Klymaxx; reggae legend Sly Dunbar are among the legions who embraced the SDSV to bring the beat that defined the times.

Forty years after the revolution began, Dr. Burgess fills us in on how it all went down.

In the '70s, searching for an acceptable electronic rhythm source was more difficult than purchasing a parka in the Sahara. For most of the decade, the best you could do was buy an early drum machine box like the Ace Tone Rhythm Ace, which seemed like it had been pulled out of a department store organ and permanently set on "foxtrot." Even the more sophisticated drum machines that began to arrive at decade's end, like the Roland CompuRhythm, were rudimentary.

And if you wanted to actually hit the electronic percussion with a drumstick, options were even more limited. There was the Impakt Percussion Synthesizer, which looked a mix between a blender and a frying pan. There was the Synare Drum Synth, suggestive of a drum stool that had transformed into a flying saucer. And there was the Pollard Syndrum, which provided the distinctive descending bloop on disco records like Anita Ward's "Ring My Bell" and snuck into occasional pop smashes like Gerry Rafferty's "Baker Street."

But these were electronic drum pads one would turn to for an extra splash of color here and there, nothing that could fill the role of an actual drum kit. Even when St. Albans-based company Musicaid released its Simmons SD-3 in 1979, the work of wily young British engineer Dave Simmons, it was still worlds away from anything you'd call a drum kit—simply two pairs of rototom-style drum pads connected to an electronic brain.

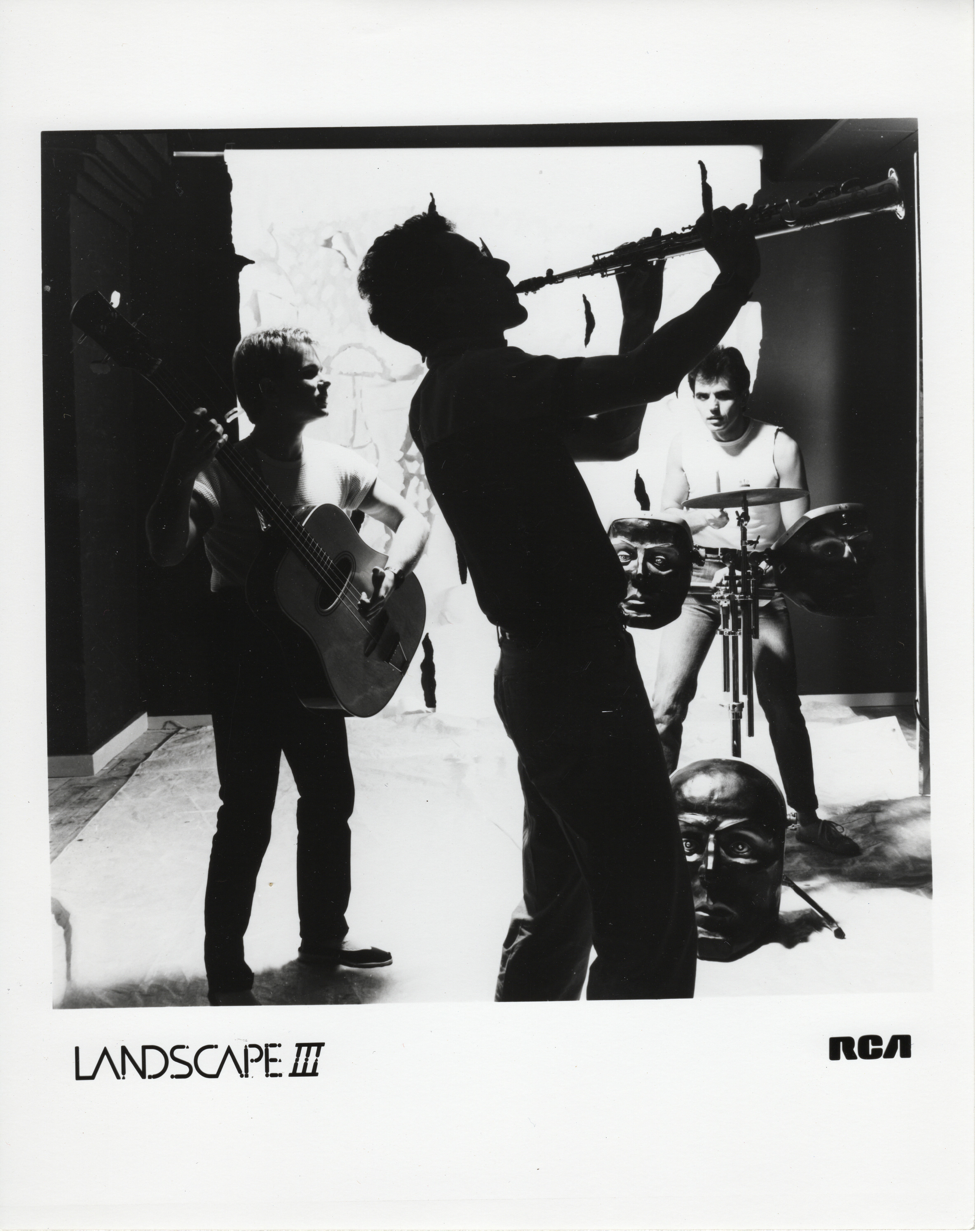

That's where Burgess enters the picture. A forward-thinking drummer then finding grassroots success with jazz-rock group Landscape, he had tried all the other electro-percussive instruments available before the SDS-3's arrival. Landscape saxophonist John Walters was playing a Lyrcion Wind Synth at the time, which was distributed by Musicaid, creating the fateful connection that brought Burgess into Simmons' orbit and set the stage for innovation that would have a lasting impact on music technology

"Recorded drums are really an electronic artifact," Burgess declares. "The instrument being played may have been acoustic but the trend since the early '60s had been towards close mic'ing and heavy electronic treatment such as compression, gating, and equalization. The sound that we hear on those records is not much like the sound you hear when you play acoustic drums.... It occurred to me that it would be game-changing to have an instrument that would spit out a [drum] sound with the impact of the recorded sound I heard when I went into the control room for playback."

Having played all the earlier electronic drums, Burgess had honed in on what was missing. "None of them really emulated or performed the function of acoustic percussion or drums because they lacked the rise time speed in their voltage-controlled amplifiers, which would impart the instant attack that is characteristic of most percussion instruments. They either had a soft attack or a delayed response, which was disconcerting if you were trying to play them in a live situation."

Before joining forces with Simmons, Burgess had contacted Syndrum creator Joe Pollard to offer his thoughts on improving the instrument by adding attack at the start of the signal. "He took exception to any suggestion that the Syndrum was less than perfect," says Burgess drolly, "and it was not a successful call."

It was while working live with the SDS-3 and its little sibling the SDS-IV that Burgess had a breakthrough.

"I triggered them from my live drum set using crystal mics that I bought for 20p from a local electronic shop," he explains. "The system worked really well and for some time [Landscape] toured with the drums being augmented with the triggered electronic sounds of the SDS synths. Effectively, I was using the acoustic drum sound for the attack component and the synthesized sound to augment the tone of the instrument. I figured out that it was possible to combine the sounds from multiple modules of the SDS-3s and -IVs that I had."

At the same time, Burgess began thinking about a full-fledged electronic drum kit:

"I had been thinking about how real drums work," he recalls, "I realized that there were several physical/sonic components at work... the stick hitting the plastic head, that is much like hitting a stick on anything hard–a countertop, whatever. It is a loud click–very sharp, sudden, and short. Then you have the first rush of air through the drum that gives another level of impact, lasts a bit longer, with more tone. The pitch and tone of [the drum] which is relative to the tightness of the head, the size of the drum, and the drum shell. Finally, there is a longer but lower-amplitude tone that is the entire body of the drum vibrating and that is related to the materials the drum is made of, the thickness of the materials, and whether there is a bottom, resonant head or not. On a snare drum, there is the additional element of the snare snapping–and sometimes buzzing, depending on tension–against the bottom head."

Burgess replicated these sounds on different SDS modules and triggered them simultaneously from a simple trigger pad. "I was pretty excited about it," he says of his eureka moment. "The sound coming out of them did what drums are supposed to do–the bass drum sound kicked me in the stomach and moved my rib cage, and the snare was like an axe through my head. Perfect."

Burgess excitedly took the long trek from London to share his findings with Simmons. "We both realized we were on to something," he says. "He started working on putting something together that would be a compact, single-purpose percussion device but that would be capable of performing the various functions of the drum set."

As a New Zealand native, Burgess had studied electronics and engineering at Christchurch Polytechnic, and had subsequently gotten his hands dirty finding DIY solutions for electronic issues he encountered as a professional musician. His tech background and drumming experience made him the ideal partner for Simmons.

"Dave put the electronics together," says Burgess, "he was technically very savvy, and it was what he did every day. My technical expertise was useful in knowing what was possible and what was not and in making suggestions."

Burgess' ideas were partly informed by a dissatisfaction at having the drums fight for a place in the live mix against instruments that could go directly through the P.A. "It came about from many conversations on the road with Landscape about why drums were still in the stone age, and all the other instruments were post-Edison technology," he explains.

The memory buttons on the front of the SDSV were inspired by Burgess' performance needs too. "[They were] something I wanted for live shows so you could have the front controls and four presets that I could set up before the show, and that would retain the sounds from show to show," he says. "Being able to change sounds from song to song was a completely new concept for drummers."

Even the default sound of the SDSV's toms, with the drop-off in pitch you've heard on a million recordings, was based on Burgess' Pearl concert tom setup. "I tuned the toms with one screw loose and that caused the pitch to drop after the initial attack," he says. "To some extent that happens when you hit a drumhead... Having a loose tension rod accentuates that effect."

Simmons and Burgess also put their heads together to create the iconic look of the SDSV's drum pads in all their hexagonal glory, though there were some surprising detours along the way. "We had discussed that the pads didn't need to be round or even have tensioned drumheads since they were not producing any sound," recalls Burgess. "The next time I went up there he had made a triangular pad with riot shield material as the striking surface."

In the experimental phase, Simmons tried out everything from batwing-shaped drums to rather creepy head-shaped drums that looked like they'd come off a totem pole.

"It struck me that the honeycomb would be a great shape because it was ergonomic," says Burgess. "The hex shapes all fit together easily, making it easy to set a kit up in various ways to suit different players. That's where the hexagonal shape came from. At that time, we didn't know that the whole synthetic drum idea would catch on, and we certainly didn't know that it would be the hex shape that would become the dominant shape and the brand image."

Ultimately, Simmons created a prototype for the SDSV's electronic brain by assembling the necessary components on circuit boards mounted to a piece of wood. By this time, Landscape had evolved into synth-pop pioneers and Burgess had begun a parallel career as a producer. The prototype was inaugurated on Landscape's second album, From the Tea-rooms of Mars…, and on his production of the 1980 single "Angel Face / R.E.R.B." by electro-dance troupe Shock, a key record in the early development of the New Romantic movement.

The SDSV went into production in 1981, by which point MusicAid had gone belly-up, and Simmons started the company that bore his name. Burgess' growing renown as a producer and—with the ascent of Landscape's "Einstein A Go-Go" to the U.K. Top 5—a pop star, he was offered plenty of opportunities to boost the new instrument's profile.

Landscape had already demonstrated the prototype in a November 1979 performance for BBC TV's futurist-tech showcase Tomorrow's World. When "Einstein A Go-Go" hit, the band's video for the song featured Burgess (who's also the lead singer) playing the creepy-heads version of the kit. And when Landscape appeared on Top of the Pops, the SDSV got another national outing.

Between his involvement with the aforementioned Shock and rising stars Spandau Ballet and Visage, Burgess was a prime mover in the burgeoning New Romantic scene. He'd already produced Journeys to Glory, the album that put Spandau on the map. For their follow-up, Diamond, Burgess made them the first band to hit the charts with the production model of the SDSV.

"I had John Keeble play SDSV with the hex pads on Spandau Ballet's first single from their second album, 'Chant No. 1,'" remembers Burgess. "Spandau then used the pads live on TOTP. From all of this the SDSV Hex pads became the house kit on TOTP, and they went viral."

In short order, Simmons kits achieved the ubiquity of lightsabers at a Star Wars convention. For the rest of the decade, the SDSV and its subsequent iterations were all over MTV, radio, and concert stages. If you wanted to be hip, you needed a hexagonal drum kit with that Simmons sound. "Having nurtured this idea over several years it was mind-boggling how it took off and how immediate the demand was," confesses Burgess.

The new generation of synth-friendly pop stars emerging in England at the start of the '80s were a natural fit for the au courant look and sound of Simmons drums. The instrument became a must for every self-respecting denizen of the U.K. Top 40, from Duran Duran and Culture Club to ABC and Ultravox.

But the Simmons sphere of influence extended far beyond British borders. Not only did the sounds supply the modern touch needed for genre-bending visionaries like Prince, they worked their way into the worlds of forward-looking R&B acts like The Jacksons, Cameo, Zapp, Klymaxx, and loads of others. Simmons kits also entered the hands of jazz-schooled, chops-heavy hands of players like Dave Weckl (Chick Corea Elektric Band) and Chad Wackerman (Frank Zappa). King Crimson's Bill Bruford literally became the Simmons poster boy, demonstrating the instrument on TV and taking it further as a stylist in a concert setting than just about anybody.

Bands on the more tech-savvy end of the hard-rock spectrum boarded the Simmons train with gusto. Van Halen's "Jump" and "Hot for Teacher" and Rush's "Distant Early Warning" are only a few of the notable rock songs of the era that feature Simmons e-drums (alongside acoustic drums and standard cymbals). And of course, after Def Leppard drummer Rick Allen's infamous 1984 accident cost him an arm, Simmons raced to the rescue with a custom-designed kit that enabled Allen to drive his band on monster hits like "Pour Some Sugar on Me."

By the time renowned session musicians like Jeff Porcaro and John "J.R." Robinson sunk their teeth into the technology, you could scarcely turn a corner without tripping over a Simmons kit. It was turning up on '80s tracks by everybody from pop/R&B songbirds Stephanie Mills and Patti Austin to jazz-pop MOR icons Manhattan Transfer.

The rest of the music gear industry paid plenty of attention to the Simmons explosion in the '80s. Drum companies and electronics specialists alike set their teams to work on getting a piece of the action, whether through their own variations on the kits or by snagging the sounds for sampling.

"Almost immediately the Simmons sound was digitized," recalls Burgess, "and you could buy Simmons sound chips for the new digital drum machines and the basic sounds were being swapped around for the digital samplers and the sampling drum machines."

In 1983 MPC Electronics came out with their Music Percussion Computer, featuring eight pads in a tabletop format not far removed from Simmons' 1981 Suitcase Kit (which was sort of a portable SDSV). MPC eventually created their own full-on SDSV-style kit, buoyed by the endorsement of drum deity Bernard Purdie himself. Around 1986 even instrument manufacturers in the USSR got their licks in, with Formanta's undeniably Simmons-esque Rokton UDS kit. Yamaha had an '80s four-pad variation on the Suitcase format too, with their DD5. Roland doubled that with their 1985 Octapad, and the same year they strode into Simmons-territory with their Alpha Drum System, its hexagonal pads looking uncannily familiar.

By the time the '90s rolled around, e-drum kits had fallen out of favor. Players were either looking once again to acoustic sources for their beats or focusing on MIDI triggers and the drum machines developed in parallel to Simmons kits. Simmons' company hung it up at the end of the '90s, having long since shifted its business away from drum kits.

Some diehards still kept the faith. In 1992, Roland introduced the TD-7, the first kit in its V-Drum line. But it was probably still a lonely time to be an electronic drummer. Something funny happened around the turn of the millennium, though. E-drum kits started seeming cool again. Yamaha unveiled its DTX series in 2000, and Roland—who had never given up on their V-Drums—introduced their TD series a few years later, a line that's still going strong today.

Along the way, sampling pads like Roland's SPD family went through the roof. Today there are tons of quality, affordable e-drum kits coming from the likes of Donner, Kat, and Alesis, and even hybrid acoustic/electronic kits like the Pearl e/Merge. Even Dave Simmons eventually got back in the business, though his kits have long abandoned the classic SDSV design.

Looking back at what his and Simmons' ideas have wrought, Burgess reckons, "I have to imagine that drum synthesizers would have happened eventually [anyway], but the SDSV definitely established a level of viability and interest as the first drum synthesizer that could perform the function of acoustic drums. I feel sure its presence sped up the process."

Assessing subsequent e-drum evolutions, Burgess says, "It's impossible to imagine that the SDSV was not the benchmark for the next generation of drum synthesizers that came out. I have to say that the new Roland electronic drums are very good. I have the top-of-the-line set and it does a great deal of what I hoped the SDSV would develop into."

Burgess has always been a bit ahead of the curve; forecasting the future, he says, "The final frontier may well be the one I was originally trying to solve—of making the live performance capabilities as or more versatile than the best acoustic instruments. I was trained in jazz and classical music and the test for me has always been whether an electronic set can respond as sensitively and in as many varied ways as a top-of-the-line acoustic set. Sounding like an acoustic set was never important to me. That's very easy to achieve today with digital sounds."

Sounding like an acoustic set was clearly never on the agenda with the SDSV. If it were, an armada of classic tunes would have sounded very different. When Duran drummer Roger Taylor says the Simmons kit "defined the drum sound for the '80s," well, he ought to know.