In 1980, a proud Leo Fender gave guitarist Tim Bailey a personal tour around his new G&L premises in Fullerton, California. "I was in awe that Leo himself would walk me through the place—it really was a big deal for me," Tim recalls, adding that he would go on to visit Leo regularly over the following 12 months to discuss G&L’s guitar plans. That first meeting had come about through Forrest White, Leo’s old factory manager from Fender, whom Tim had met six years earlier.

At Fender, then at Music Man, and finally at G&L, Leo and his colleagues regularly consulted local players to find out what they wanted in a guitar. It was hardly a new idea, but it’s one that Leo knew worked, and one he valued.

Tim, who is now 67, was in his late teens when he began working as a guitar teacher and part-time repairer for McFarland’s music store in Riverside. He played in bands, he recorded as a session guitarist in local studios, he played cello in four local orchestras. And he met Forrest White and Leo Fender.

One day in 1974, a McFarland’s customer traded in a Fender-like steel guitar and amp, but each had a White brand. Fender had made these Studio Deluxe-like steels and Princeton-like amps in the mid ’50s as a shortlived sideline to sell to non-Fender dealers, replacing the customary brand with "White" as a nod to Forrest White.

McFarland’s offered the pair to Fender, figuring they might want them as historic items, but they weren’t interested. They did, however, suggest calling Forrest—who arrived at the store half an hour later and promptly bought both for his personal collection.

Tim and Forrest struck up a friendship as a result. Forrest and his wife Joan would often go see Tim perform—at Prado Park, say, with Tex Williams, at the Fairgrounds with The Californians, at Disneyland with The Crownsmen, and many more.

"Forrest was VP at Music Man," Tim says, "the company funded by Leo—secretly, at first—and by ’78 I was manager of the music department at the Berean Christian Bookstore in Santa Ana. Forrest and I started going to lunch every other Friday at a Black Angus restaurant near my store, where Forrest loved to eat." And that’s where Forrest told Tim stories about his early days with Leo at Fender and about his current gig at Music Man.

"Forrest told me how Leo had hired him in 1954 to run the Fender plant, because Leo wanted to focus 100 percent of his energy on inventing and designing," Tim continues. "Leo was not an outgoing guy, and he didn’t like having to deal directly with the people and the logistics of manufacturing. Forrest monitored and tracked the inventory, dealt with buyers, vendors, and employees, and he made the place run smoothly. He’d previously designed the assembly and production line for Rohr Aircraft in Riverside. Forrest helped convert Fender into a real factory, which grew and grew over the years, until he’d had enough of the suits at CBS and quit in 1967."

Tim went into the Music Man premises a few times with Forrest, and met Forrest’s partner at the company, Tom Walker, another ex-Fender man. Music Man had begun production of amplifiers in 1974, and two years later Leo Fender’s CLF outfit began manufacturing guitars and basses for the company.

"I can still remember about the turmoil at Music Man when Leo refused to make instruments for them any longer," Tim says. "I interacted with Tom a few times back then, and it was clear Tom and Leo were just not seeing eye to eye. Tom wanted things the way he wanted them, and he simply did not consider Forrest his equal. Forrest wasn’t perfect, but he was a hard worker and a street-smart guy who was Leo’s plant manager for over a decade. Tom was a former salesman and an idea guy. It seemed to me that the growing conflict between Tom, Forrest, and Leo eventually destroyed Music Man and led to its eventual sale to Ernie Ball in the early ’80s."

Forrest took Tim to meet Leo toward the end of 1979, by which time Leo—in partnership with yet another ex-Fender stalwart, George Fullerton—was moving toward what soon became G&L. Into 1980, and Leo gave Tim the personal tour. "It was clearly in the early stages, but he took me around and introduced me to the guys there. I remember the setup being kind of modular—but I was in awe that Leo himself would walk me through the place! It really was a big deal for me."

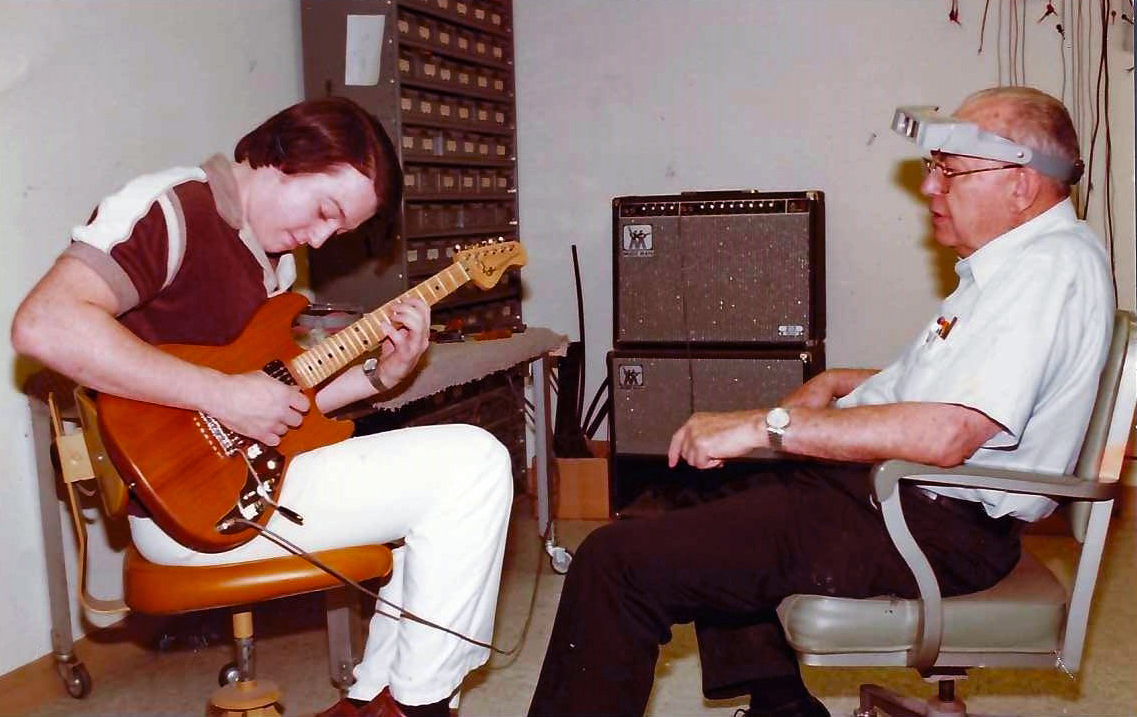

After the tour, Leo sat Tim down in his workshop and talked through the prototypes for what became the F-100, G&L’s first guitar. "I was very much a detail nerd and was interested to know why he chose particular things, which I guess he enjoyed being asked because he was forthcoming in his responses."

When it went into production, the F-100 was offered with two fingerboard radiuses, at 7 1/2 inches and a flatter 12 inches, options Leo had already used on Music Man guitars. "However, Leo was not a fan of flatter fingerboard-radius options," Tim recalls. "When we spoke, he was not certain he would continue the 12-inch option with G&L—he preferred a rounder 9 1/2 option instead."

He asked Leo why he hadn’t pursued the idea of noiseless single-coils. "Leo felt the compromise in tone was simply not worth the results at that point. Of course, we know today how the technology has changed drastically, with the emergence of advanced ghost-coil design and so on."

When it came to tonewoods, Tim was surprised that Leo agreed with his own view that different body woods in solidbody electrics made minimal difference in tone. "That’s why he used whatever wood was available for his body blanks. Over the years, Leo made his guitars out of pine, alder, ash, poplar, mahogany, and so on. When I asked why, he said he preferred what was readily available—and affordable. And when he measured responses on his scope, he didn’t really see differences between woods. Remember, Leo was partially deaf by then, and he never learned to play a guitar, which may have influenced his feelings on the subject. However, I still agree with him."

They found another area of mutual agreement. "I asked Leo why they moved to synthetic nuts at Fender rather than stick with bone—and of course I was asking about the early ’60s at Fender; G&L embraced both synthetic and bone options. Leo referred me back to Forrest to confirm that switching to synthetic was not a cost saving move, but was for more consistency and better quality control. And it actually cost them more, at least that first year, than actual bone."

Tim says that before the first meeting with Leo, Forrest wasn’t even sure if Leo would give him the time of day. But in fact the two men got along famously over the next year and a half.

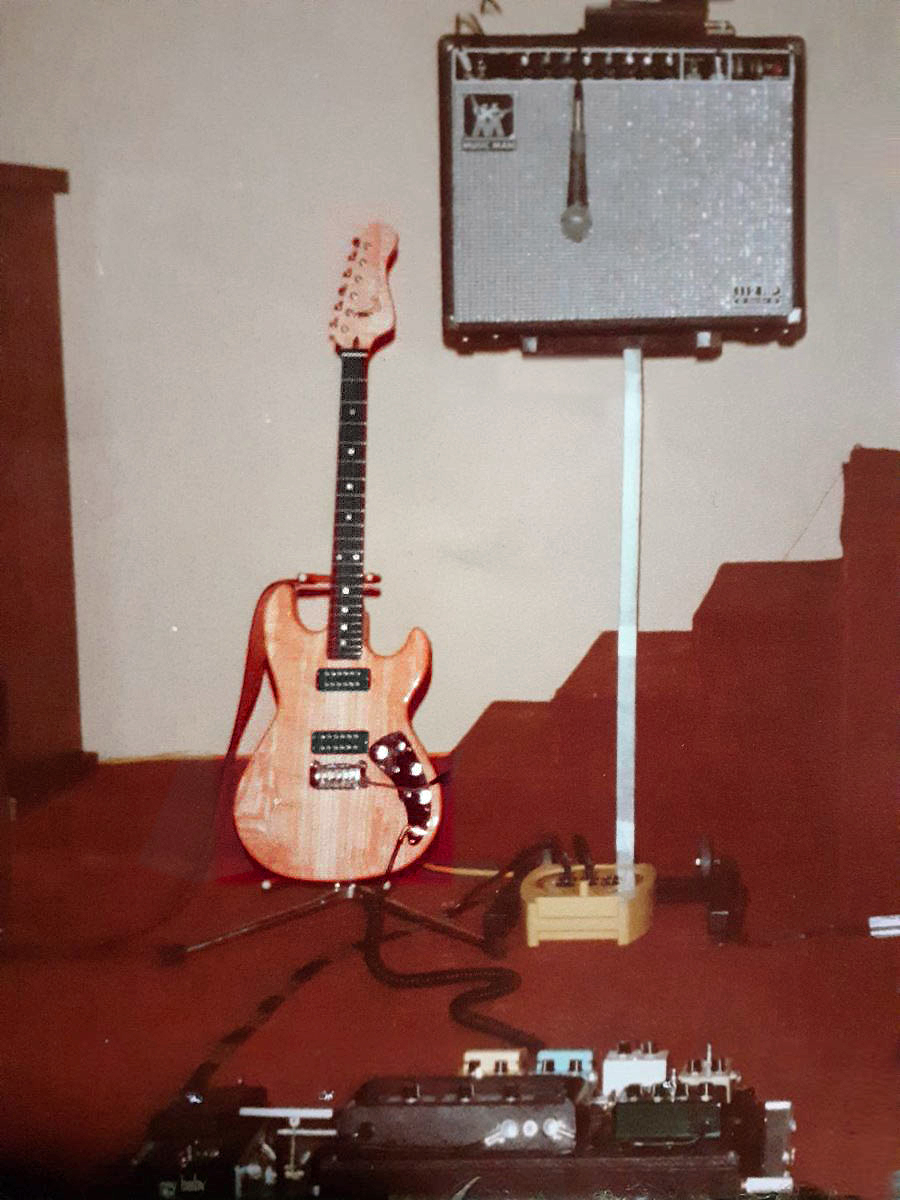

The F-100 went into production during 1980, available with options for vibrato and active preamp. Tim had a nice surprise on his 25th the following year when Forrest turned up with a birthday gift of a Music Man 65-watt combo—plus, from Leo, a custom G&L F-100.

Tim’s special F-100 had no serial number, a nicely figured one-piece swamp ash body, an ebony board, 12-inch radius, Dunlop 6290 jumbo frets, and passive electronics with coil-split, usually only offered on the active version. "I sold the guitar in 1989 to my friend Jessie in Victorville," he recalls with a groan. Why was that? "Because I was in my 20s and really foolish. I should have cherished it and never sold it!"

Around this time, Tim got married and moved to Palm Springs for work, and he lost touch with Leo and with Forrest. Fast forward to 1994, and Tim’s final conversation with Forrest came out of the blue. He happened to be visiting his parents in Riverside one Saturday evening when the phone rang.

"I answered, and it was Forrest, who wanted to sell me a water-softening system. I politely declined, and asked how he was doing. Anyway, it was many years before I looked him up again, and then I realized he had passed away, very close to that last conversation."

Forrest died in November 1994 at the age of 74, a little over three years after Leo Fender’s death. Leo’s first wife, Esther, had died in 1979. "When Esther passed away, Forrest and the guys were very protective of Leo," Tim says, "because he was having a really hard time adjusting to the loss. Then, along came Phyllis, who was considerably younger than Leo. Many of the guys were concerned she might be looking to cash in, as Leo was a high profile businessman."

Leo and Phyllis married in 1980, and Tim says Phyllis proved them all wrong. "She was sweet to Leo, very protective and loving—all of which he really needed at that time. In addition, she supported him until the end, and she continued to be a wonderful ambassador for Leo, and his brands, for many decades after his passing. Phyllis, who died in 2020, will be sincerely missed."

About the author: Tony Bacon writes about musical instruments, musicians, and music. His books include Electric Guitars: Design & Invention and Legendary Guitars. Tony lives in Bristol, England. More info at tonybacon.co.uk.