The appearance of magnetic tape recorders in the late '40s stimulated a whole new musical language, and by the mid-'50s, there were tape-based electronic music studios in France, the United States, Germany, and elsewhere. In the UK, though, interest was confined to a few questing individuals, including Daphne Oram and Desmond Briscoe, both BBC staff members. Through 1957, while working out-of-hours creating electronic sound for pioneering BBC broadcasts, the pair lobbied the corporation to create its own electronic music studio.

When the BBC Radiophonic Workshop opened on April 1, 1958, at the BBC studio in Maida Vale, west London, there was a sense of giving in to tiresome zealots. Dick Mills, the longest-serving member of the Workshop staff, told me about the unspoken but implied BBC attitude, which was: "Why don't we give them a room somewhere—and let them get it out of their systems?"

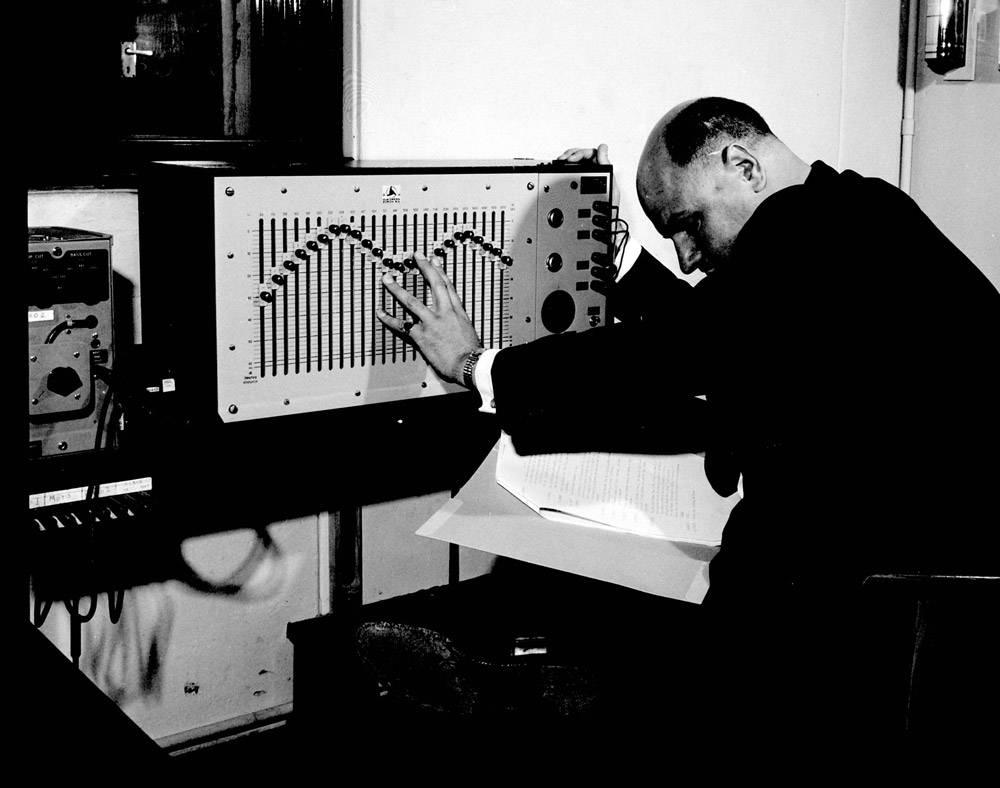

The Workshop was equipped with tape recorders, turntables, oscillators—the tools of the '50s electronic musician—but in this case secondhand, obsolete, and sometimes broken. The mixer, for example, was a pre-war antique with an oak body and had once been installed in the Royal Albert Hall.

From such inauspicious beginnings, the Workshop made a swift impact, and large audiences began hearing radical electronic music. Screenwriter Nigel Kneale made notes for sound design for his BBC television serial Quatermass And The Pit (1958/'59) such as "electronic vibration with occult noises." Briscoe, assisted by Mills, interpreted these with spliced and reversed recordings of feedback, echoed drums, and disconnecting amplifiers. The final episode was watched by a fifth of the UK's population.

Oram left within a year, but others soon joined, including Delia Derbyshire and Brian Hodgson. It fell to Derbyshire, assisted by Mills, to realise composer Ron Grainer's theme for a new children's sci-fi television series. Grainer delivered a single sheet of paper, with a bassline, a melody, and instructions to convey atmosphere, such as "wind bubble" and "cloud."

From this, Derbyshire, with Mills again, took two weeks in August 1963 to create the most recognisable piece of British electronic music. The Doctor Who theme was first heard on November 21 that year, at 5:15 p.m., and remained in service (with various reboots) until 1980. Hodgson, meanwhile, created the equally famous sound of the TARDIS dematerialization from a recording he'd made by scraping a key down a bass string of a broken piano.

Through the '60s, electronic music edged away from tape composition toward voltage-controlled synthesis. The Workshop's composers, managed by Briscoe, observed with interest, and in 1969 there was talk of buying a Moog. It came to nothing, due to cost, bureaucracy, and perhaps reticence from Briscoe himself. Instead, the Workshop turned its attention to Electronic Music Studios (EMS).

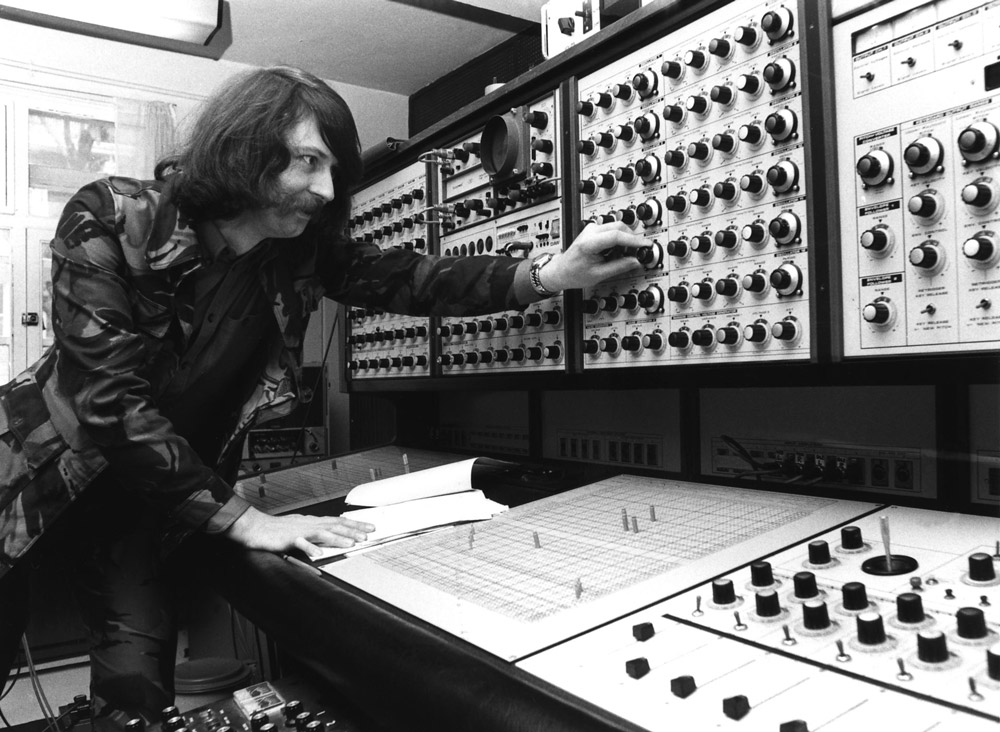

Founded in 1969 by Peter Zinovieff, Tristram Cary, and David Cockerell, EMS had ties with the Workshop. In 1966, Zinovieff had formed Unit Delta Plus with a moonlighting Derbyshire and Hodgson. The trio created electronic music in a studio in the garden of Zinovieff's house in Putney, south-west London, which backed onto the River Thames. Cary had been making electronic music years before the Workshop formed and built probably the first electronic music home studio in England. Though never a Workshop member, he often visited, and he worked regularly on Doctor Who.

Based at Zinovieff's Putney house, EMS produced the joystick-controlled VCS3 in 1969, which was priced less than the new Minimoog. The Workshop purchased several VCS3s and later a Synthi 100, a huge modular system known as the Delaware, and the new technology contributed to a changing of the guard. Sixties stalwarts Hodgson and Derbyshire were gone within a few years of the synths' arrival. Derbyshire was primarily a tape composer, and she never fully embraced synths. Hodgson did, but he decided—for a while—to explore their potential elsewhere.

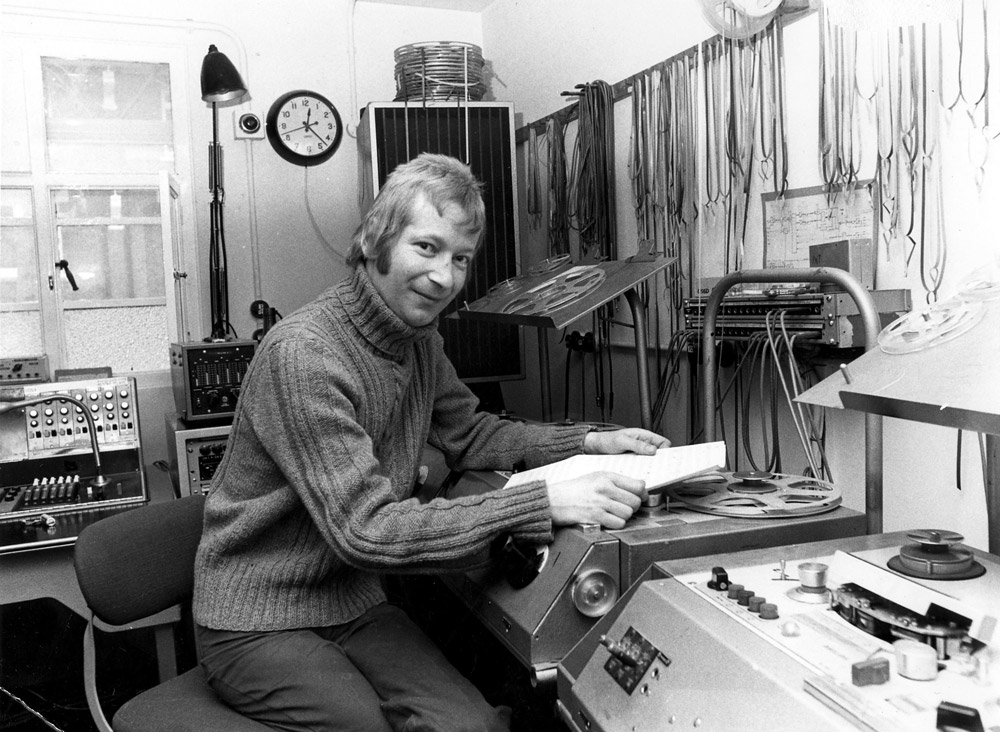

It fell to a new generation, including Paddy Kingsland, Roger Limb, and Peter Howell, to take the synths in hand. The synths were quicker compositional and recording tools than tape, but they had their quirks. So sensitive was the Delaware to temperature that it was prone to going out of tune when the studio door was opened. Even so, it was widely used, including by Kingsland on the (recently reissued) soundtrack to the children's television series The Changes (1975) and for effects on the original radio series of The Hitch-Hikers Guide To The Galaxy (1978).

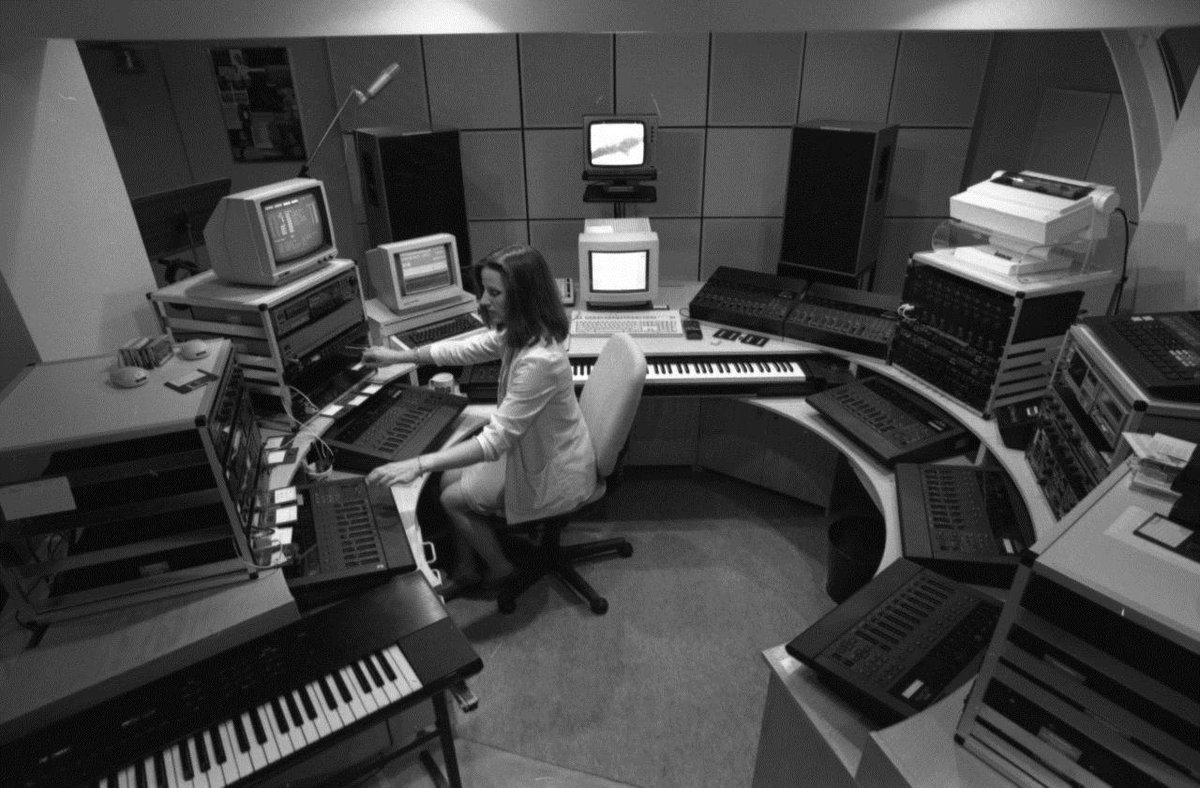

Briscoe retired in 1977, replaced as Workshop Organiser by the returning Hodgson. In his five years away, Hodgson had made electronic music commercially, with some success. He found a Workshop that now contained expensive equipment, but it retained a cobbled-together feel. Hodgson knew that synth development was accelerating. The once-futuristic Delaware looked like a dinosaur by the end of the '70s. He methodically retooled the Workshop, and by the mid-'80s he had his composers working in studios with Yamaha DX7s, at least one Fairlight, and Apple Macs.

Traditionalists grumbled, but Howell told Sound On Sound in 2008: "There's still this prevailing idea that we were somehow almost traitors for using modern gear and computers! Some people still believe that the original Workshop … was the only incarnation that mattered. But … why on earth should I spend three weeks chopping up little bits of tape to get exactly the same result? We had to catch up with the real world."

A high-profile product from this era was Elizabeth Parker's score for David Attenborough's The Living Planet (1984), which made extensive use of the PPG Wave 2.2.

As the cost of electronic music equipment fell in inverse proportion to its availability, a new generation of freelancers set up home studios of a sophistication once unimaginable. Electronic music was no longer the preserve of the big professional studio.

John Birt, who was appointed as the BBC's director-general in 1992, initiated measures intended to make the corporation run more like a commercial business. Birt's BBC evaluated departments according to their economic efficiency, and the Workshop couldn't compete financially with freelance composers. It could artistically, though, and continued to work on flagship projects such as Michael Palin's Full Circle television series (1997). But its influence was waning. In the Workshop's '70s heyday, there were 300-plus commissions per year. In 1997, there were just eight.

Hodgson left in 1995. The following year Mark Ayres, a composer who had worked on Doctor Who in the late '80s, was summoned. He told me: "There were three rooms of sketchily catalogued tapes, and there was a move to dispose of them. I was called by Peter Howell, Paddy Kingsland, and Brian Hodgson—individually, but in quick succession—asking if I would take on the cataloging and preservation, as they'd found a friendly ear in BBC Radio Production Resources, Colin Duff."

The tapes, catalogued and labeled by Ayres, were moved from Maida Vale to the BBC archive on April 1, 1998, 40 years to the day since the Workshop had first opened. By this time it was history. Ayres said: "At the last, it was just Peter Howell and Elizabeth Parker left, working on Full Circle. Peter had a home studio, and completed his work there, so Liz was the last person at Maida Vale. She was made redundant before the programmes were completed, so she finished the job as a freelance, renting her studio back from the BBC until it was done."

Almost as soon as it was gone, the Workshop was nostalgically eulogised. Compilations were issued on CD, while magazine articles contributed to developing cults around Derbyshire and Oram in particular. A TV documentary,The Alchemists Of Sound (2003), featured Workshop alumni reminiscing about their glory days. Oliver Postgate, of Bagpuss and Clangers fame, was the narrator, a choice that underlined the programme's positioning of the Workshop as a peculiarly British example of homespun creativity and ingenuity.

Fittingly for an institution so connected with Doctor Who, in May 2009 the Workshop reconvened in a new form. Ayres rounded up Limb, Kingsland, Howell, and the venerable Mills for a concert at The Roundhouse in north-west London. Billed as The Radiophonic Workshop, the quintet, backed by a brass section and drummer, performed arrangements of BBC highlights, including Hitch-Hikers and Doctor Who, alongside new compositions.

This incarnation of the Workshop continues, with live performances and a 2017 album of new material, Burials In Several Earths. And the London Contemporary Orchestra performed a Pioneers Of Sound concert during 2018's Proms at the Albert Hall as a tribute to the Workshop and including works by Oram and Derbyshire.

Meanwhile, in a situation mirroring the afterlife of so many heritage rock bands, in 2012 Arts Council England and the BBC launched the New Radiophonic Workshop as an online venture, under composer Matthew Herbert as creative director. Herbert's first work took audio from 25 previous Workshop projects to create what he described as a "curious murmur of activity."

About the author: Mark Brend is an author and a musician. His most recent book, The Sound Of Tomorrow (Bloomsbury 2012), explores early commercial electronic music. He lives in Devon, England.

Mark Brend would like to thank Mark Ayres for help with this piece.